Do Beliefs Grow on Trees?

A Challenge

I've come up with a frightfully difficult exercise and if you enjoy a real challenge, I hope you'll try it with me.

Here's the basic idea:

Make a tree of your beliefs such that each is supported logically by one below it. More foundational beliefs will be on the bottom and the beliefs above should be derived from them.

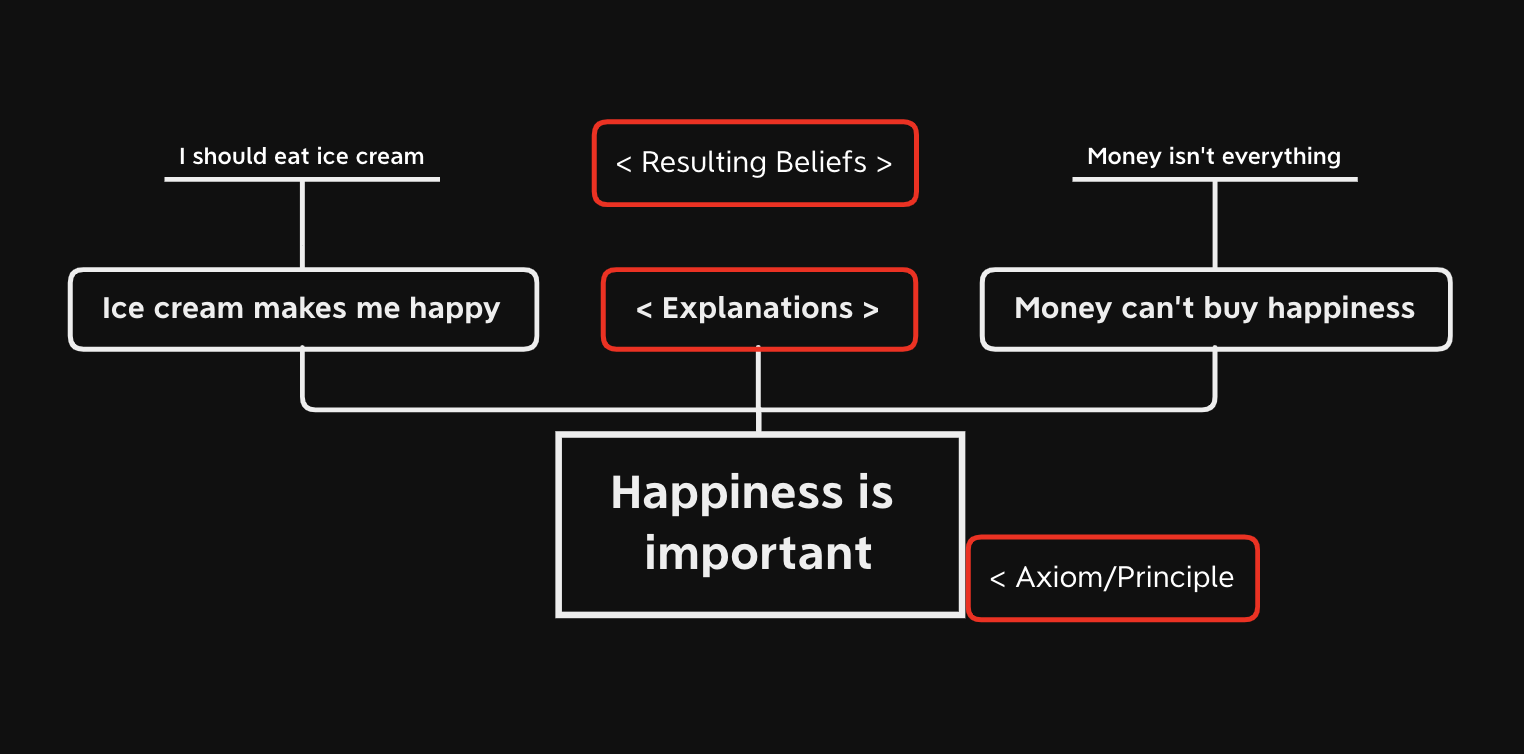

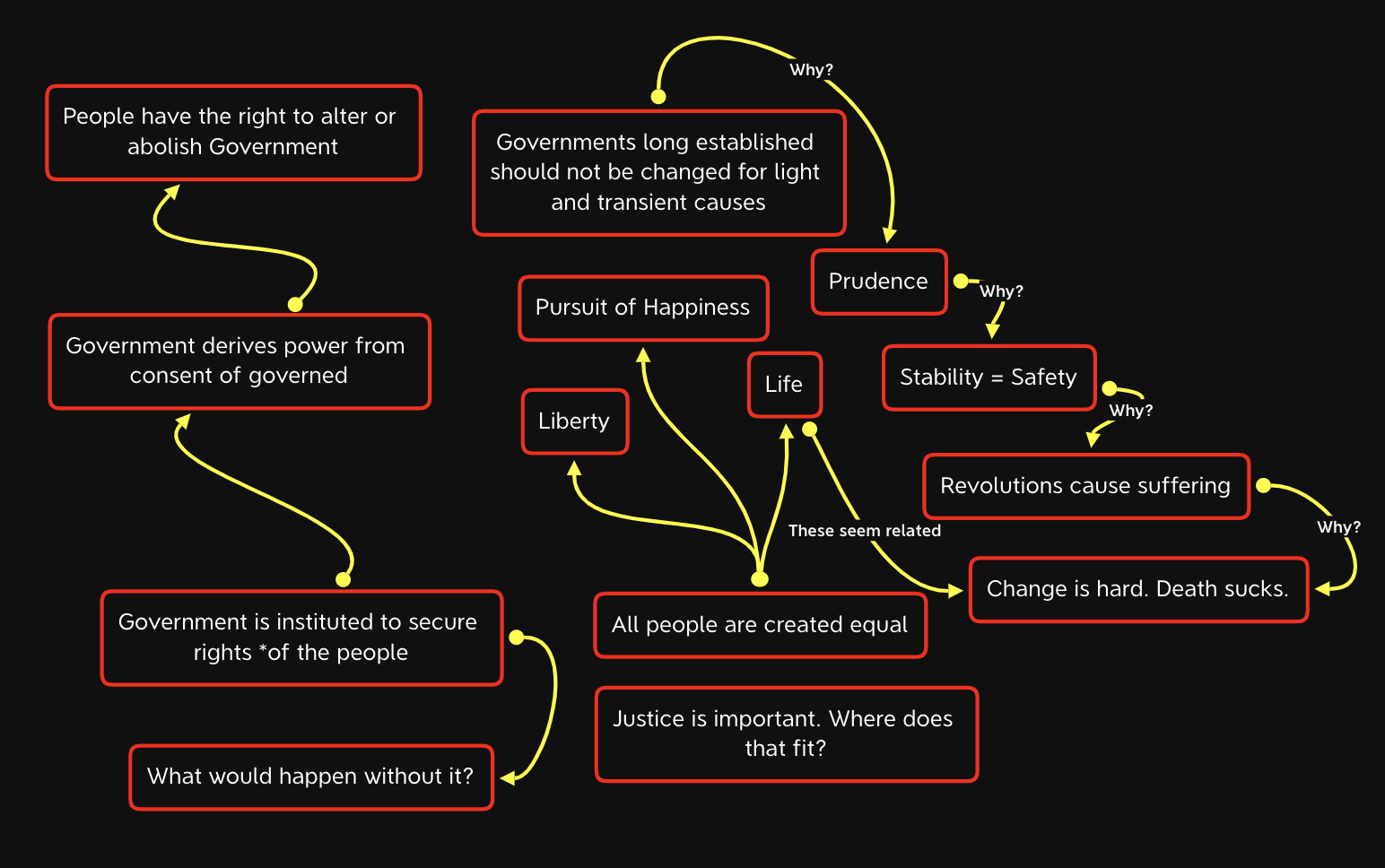

Here's a quick example:

This seems simple at the beginning. I like to think that my beliefs arise out of reasoning, rather than my reasoning out of beliefs. I am now not so sure. The longer I spend on this, the more I realize how occasionally fuzzy my model of the world has been. Squeezing out bias is difficult, and this process can sometimes feel like pulling the chair out from under yourself. So here are a few of the benefits to help you psych yourself up to try it:

Discomfort – Yes, this is good. The more accustomed we become to pushing against mental resistance, the more we become comfortable with the difficult actions that truly matter.

Consistency – Everyone wants to be consistent. This entire exercise is about examining your consistency and being able to verbalize your thoughts in a sensical way.

Humility – To admit when you are wrong is usually not easy. But being able to set aside competitiveness and update your outlook is actually one of the best long-term competitive advantages you can have.

Growth – By tracking your progress in a visual format, there is a source of encouragement and progress. And also probably an overall trend of actual growth.

Conversation Preparedness – If you ever find yourself in an elevator being asked for a summary of your life goals, the story is organized and ready in your mind.

How do I do this?

Get out a pen and paper, or use mind mapping software such as XMind, LucidChart, or MindMaster.

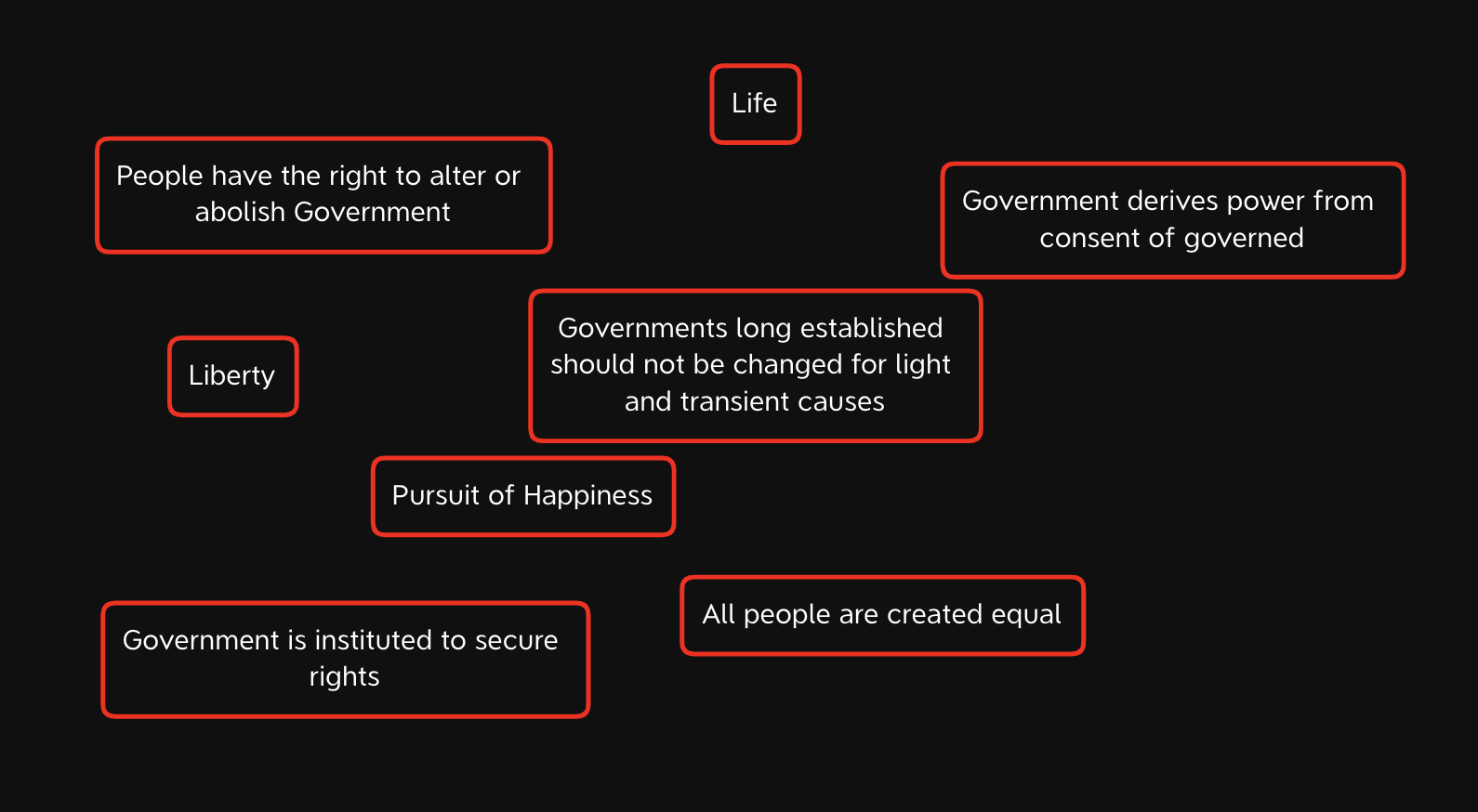

The easiest place to begin is by listing ideas. Without worrying about their relations, write down any theories, opinions, principles, or even simple words that you believe in. They can be specific or general. If you find yourself already having trouble, try this time tested technique to unleash opinions: think political.

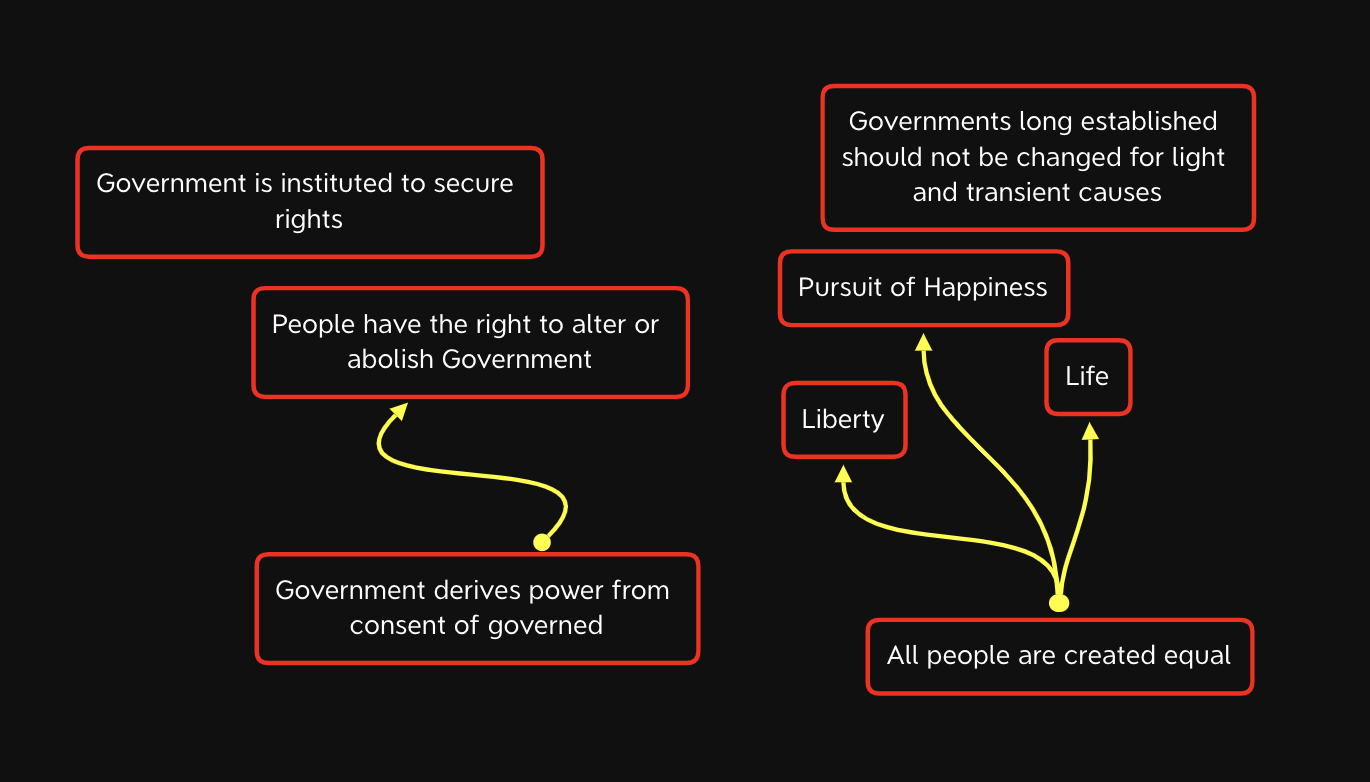

Which ideas are the most foundational? If it makes sense, move these core beliefs toward the bottom. If there are any other ideas that are clearly results of these, make a connection.

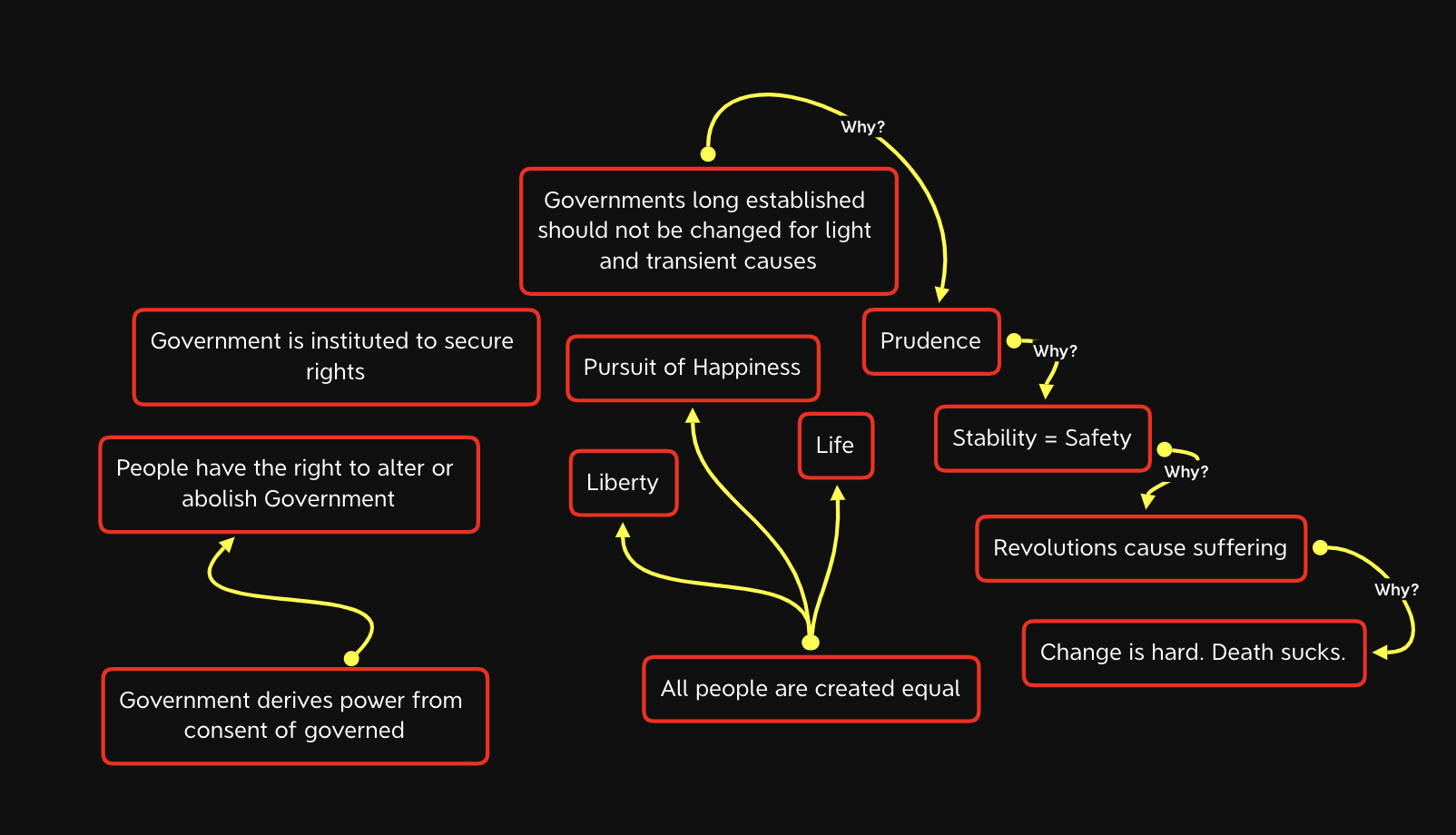

Choose an idea and ask yourself why you believe it to be true. This may lead to a deeper belief. Repeat until stumped. If the belief is a truism, you may have found an axiom in your thinking. Take some time to put it under a microscope. If you are just having a difficult time explaining why you believe something, you might have discovered a gap. Awesome! This is a sign of progress, the real reason why you are doing this exercise.

Look again at your graph as a whole and think about what might be missing, where you have questions, or where you could add structure. Maybe apply some Socratic Questioning.

You may be noticing that a mess quickly accumulates and that it looks nothing like a tree. I would call this stage a belief graph. The tree will not be formed after a single pass, but you can repeat these techniques as needed. Be willing to return a day, a month, or even years later to attempt revisions. The end goal is to mold the graph into a consistent belief hierarchy. As far as I can tell, this is a very long term project.

Thought Bureaucracy

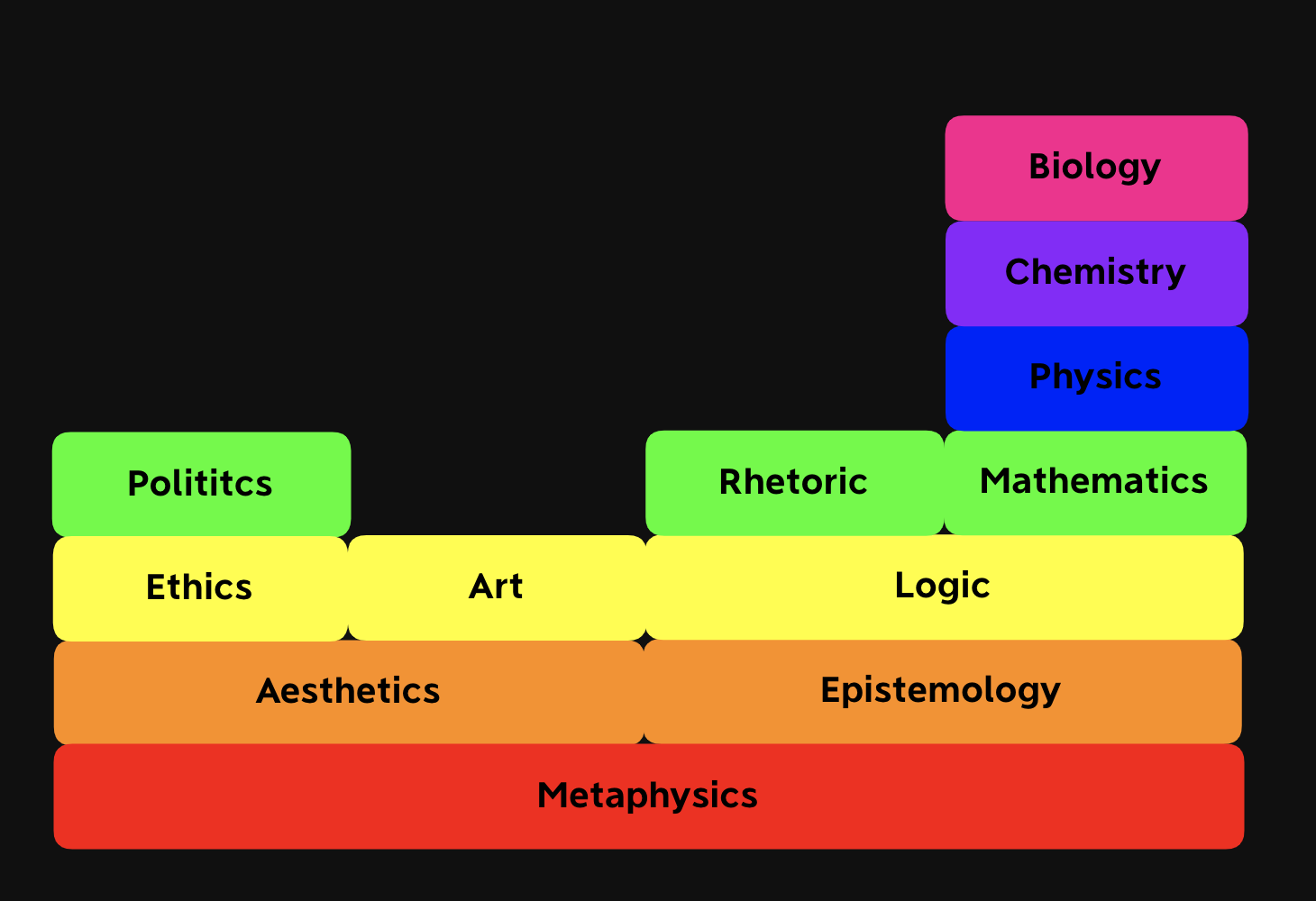

It is so long term, in fact, that I question whether or not it is possible. What if the concept of a hierarchy was where this exercise went wrong in the first place? It seems highly possible that attempting to order ideas hierarchically is actually what leads to bias. As a subscriber to the brain-equals-hardware-mind-equals-software metaphor, it is enticing to imagine a clean software stack:

In this diagram, each field of study is a manifestation of the one below. At least in the upper right portion, the ordering of subjects is relatively agreed upon. But after looking around for even a minute, it is easy to find criticisms of the ordering. For example, rhetoric uses not only logical appeals, but emotional appeals, so it should have some connection to aesthetics. Deciding on a single organization is very difficult and is bound to leave out important connections.

Another problem with forcing a hierarchy is the illusion that the lower items are necessarily more important. Metaphysics might be all-encompassing, but it is much more important for the average person to understand basic financial math than to understand whether or not the property of being red is an instance of a universal redness.

Hierarchical thinking also discourages "communication" between different areas of the tree. Consider a corporate structure: whether vertically or horizontally separated, employees will not have as much interaction with those in other segments. CEOs and factory workers rarely speak and a marketer will talk less with HR than with other marketers. In the diagram above, there is something similar: thought bureaucracy.

As an example, thought bureaucracy can be responsible for false dichotomies, such as the one that often separates STEM and the arts. Given the diagram above, one must travel all the way down to the first common parent, metaphysics, in order to find any connection. If you are constricting your thinking to hierarchies, you are promoting thought bureaucracy.

Hierarchies are nice. They are easy to navigate and pleasing to the eye. And in the case of a belief hierarchy, they ensure structured reasoning. But, in general, rigid use of this format is bound to encourage oversimplification and suppress creative synthesis.

A Better Shape

To understand why hierarchies are limited, we should step back and look at what makes them so tempting.

The root of thought bureaucracy lies in mistaking it for reasoning from first principles.

To reason from first principles is to break down a problem into its parts and reassemble them so as to reason beyond what is visible on the surface. This was largely the inspiration for this post's exercise. The tree shape was used in attempt to ensure a one-way flow of reasoning.

To borrow some terms from graph theory, the tree we were trying to build was...

- Directed: Edges have arrows (i.e. there is flow of reasoning)

- Rooted: There is at least one vertex that cannot be reached by taking any path except starting at itself. [A] (i.e. first principles are not deduced from anything else)

- Acyclic: There is no path from one vertex back to itself (i.e. no circular reasoning)

- Connected (Weakly): There is an undirected path between any two vertices (i.e. no islands)

- Injective: There is only one path from a root to any other vertex (i.e. one parent per belief)

The technical term for this shape in graph theory is an arborescence. The ideal shape of a belief graph should be directed, rooted, and acyclic, which is where it works well. But being weakly connected and injective are both downsides to visualizing belief with an arborescence. And it turns out that they are not necessary to maintain consistent reasoning from first principles.

A graph with all of the characteristics of a tree except connectivity is called a forest and is more useful. Not everything necessarily needs to be connected the entire time. Islands allow for outlier ideas to grow on their own. They might eventually connect to the mainland, but as long as each island has a strong foundation in first principles, it is viable [B].

The biggest weakness of an arborescence is injectivity, because this is the cause of thought bureaucracy. Once beliefs can have more than one parent, they can connect with other branches (horizontal) or levels (vertical) of the graph, as long as they don't connect upstream. This will significantly increase the potential size (# of vertices) and order (# of edges) of the graph. This is good because you no longer have to stretch beliefs to fit the restriction of a single parent. They can be proven more thoroughly and flexibly.

Removing injectivity also has a very interesting consequence: a belief can be reached by multiple independent proofs. This is more than just a curiosity. A new proof, although it proves the same statement, sheds light at a new angle. And a belief that is reached by many proofs stands out as having a strong foundation and a central role to your thinking. This is an important feature to look for when building your graph.

The technical term for the one-way web with these characteristics is a directed acyclic graph, or DAG. Forget the belief hierarchy. The goal of the exercise should be to create a directed acyclic belief graph (DABG?).

Trees Have Roots

From Farnam Street: "A first principle is a foundational proposition or assumption that stands alone. We cannot deduce first principles from any other proposition or assumption."

But we can induce them. And this could mean our DABG has roots.

Consider axioms in math. Although they rest at the "bottom" of math's DABG, they were not the first mathematical ideas to exist. While it is nice to believe that we start with obvious, generalized axioms, the reality is that those often come later as results of specific observation followed by induction [C].

I recommend recording not just the extremely logical beliefs, but also the experiences that led to them, even if they are not perfectly logically consistent. Be honest with yourself. If some experience or set of them has helped you theorize something, that was the source of the theory.

The roots are the life experiences that can alter generalization. Comparing them with others can make it clear when one of your beliefs is based on faulty induction from a limited set of experiences.

In Summary

The DABG is an incredible tool for self-improvement. If everyone did this, the world would be a more thoughtful and humble place.

So,

DO make a visual representation of your beliefs. DO update it often. DO rigorously ensure its consistency. But DO NOT attempt to squeeze it into a strict tree.

Notes

[A] In a directed graph, this is actually a consequence of being acyclic and nonempty.

[B] All islands need to have a first principle. By definition they will, but this seems like it still needs attention. There is a large difference between a belief without evidence and a principle without application. Be sure that the "first principle" is truly obvious.

[C] Now pause. Since I just got done spewing about critical rationalism, I had better explain that induction is impossible. All observations are theory laden so observations are actually propositions/assumptions. What is actually happening is that we are simply guessing and then refining our guesses when they seem wrong. Ok, that sounds much better. But either way it is often true that in order to reach first principles we first reason from specific experience and up toward theoretical generalizations.

Comments:

Tweet